Transformation of Russia; East Europe, 1989 –

In addition to showing which plays have become gateways to social activism, this platform also puts in dialogue the goals behind massive street protests in the region today and the social goals of the protests in 1989. This section of the digital platform shows how the middle class in East Europe now is more politically active than at the fall of the Soviet Union, as demonstrated by the Maidan protests in Ukraine in 2013, the protests in Belarus in 2020, and protests in Russia from Pussy Riot forwards.

The 1989 protests led to some East European countries’ post-Soviet identity formation. Can the recent protests in the first quarter of the third millennial lead to identity formation of East European countries, or are theatre and performance art more effective in identity formation among classes of people in the region?

May 6, 2012

Exercises of social critique and dissent were practiced on May 6, 2012 in a massive protest – one of Russia’s largest in history – against Putin’s unconstitutional third term as President. The protesters marched along Iakimanka Street towards Bolotnaia Square, the planned location of the concluding rally.

The organizers had sought approval of authorities for organizing the event but this did not prevent the demonstration from being dissolved by the police. The protest leaders understood that for a moment they, not the Kremlin, were dictating the political agenda. In Moscow the police estimated the crowd at 25,000, though organizers said there were more than twice that many. About 600 were arrested, including opposition leaders Alexey Navalny and Boris Nemtsov. After Navalnyi had been arrested, a journalist read the address that Navalnyi had prepared ahead of time: “Everyone has the single most

powerful weapon that we need — dignity, the feeling of self-respect. It’s impossible to beat and arrest hundreds of thousands, millions. We have not even been intimidated.” Twelve protesters in an antigovernment rally on Bolotnaia Square were put on trial in June for taking part in mass unrest.

The demonstration, and its earlier protests in December 2011, marked a watershed moment, ending years of quiet acceptance of the political consolidation Mr. Putin introduced. “Older participants were reminded of the oceans of demonstrators who marched on the Kremlin in the early 1990s, heralding the collapse of the Soviet Union” (Ellen Barry, “Rally Defying Putin’s Party Draws Tens of Thousands.” The New York Times. Dec. 10, 2011).

Euro Maidan

Euro Maidan, the name for the massive protests in Kyiv in the winter of 2013, is composed of two parts: “Euro” is short for Europe and “Maidan” refers to Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), the large square in the downtown of Kyiv, where the protests mostly took place. The word “Maidan” is a Persian word meaning “square” or “open space.” Ukraine’s pro-European trajectory was abruptly halted in November 2013 when a planned association agreement with the EU was stopped just days before it was scheduled to be signed. The accord would have more closely integrated political and economic ties between the EU and Ukraine, but Yanukovych bowed to intense pressure from Moscow. Street protests erupted in Kyiv. Police violently dispersed crowds in Kyiv’s Maidan.

Yanokovich fled Ukraine. There ensued a scramble for power, ongoing pressure from Moscow, and battles between separatists who want to join Russia and “Nationalists” who want to break from any Russian influence in order for Ukraine to be a part of EU. Zelinsky became president in 2019. On January 16 th 2014 the authorities passed repressive lays against civil liberties, freedom of speech, and public gatherings. They gave the Maidan protesters an ultimatum: to disperse or be dispersed by riot police. On

January 19 th , 2014 masses rallied in Maidan. The authorities ignored the demands of the protesters.

In March 2014, large swaths of the Donbas became gripped by pro-Russian and anti-government unrest, and many in Ukraine feel the war began in 2014. In February 2022 Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. On 30 September 2022 Russia unilaterally declared its annexation of Donbas together with two other Ukrainian oblasts, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. This is the biggest war in Europe since 1945.

Kowal, P. et al Three Revolutions: Mobilization and Change in Contemporary Ukraine: Theoretical Aspects & Analyses on Religion, Memory, & Identity. Stuttgart: Verlag, 2019.

Gezi Park Protests

In May 2013 a group of activists staged a sit-in at Istanbul’s Gezi Park, protesting the Turkish government’s plans to demolish the park to build a replica of the Ottoman-era Taksim Military Barracks that would include a shopping mall. The forced eviction of protesters from the park and the excessive use of force by police sparked an unprecedented wave of mass demonstrations. 3 million people took to the streets across Turkey over a three-week period to protest how the government was handling environmental concerns. Many people protested against not only the government’s urban development plans but also its refusal to allow citizens any influence over the restructuring of public urban spaces. Others protested the government’s intrusive practices and infringement upon democratic rights and individual freedoms.

After these protests died down, activists had to adapt to a difficult political context. Many focused on local municipal issues and environmental concerns, while some civil society organizations focused on the more general state of Turkey’s democratic regression. Most activists, however, chose to adopt a lower profile as repression increased and the space for activism narrowed. In Turkey, post-protest attempts to form a new political party did not succeed.

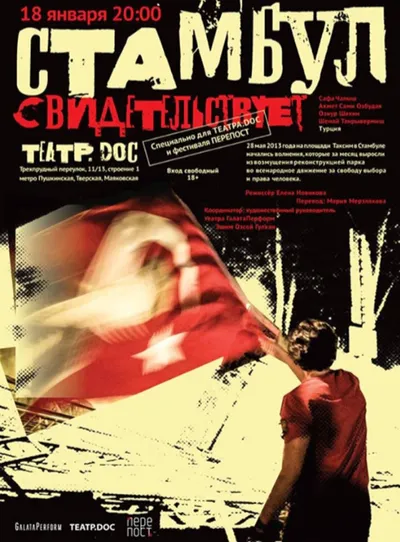

In January 2024 Teatr.doc created Istanbul: Eye Witness Theatre, based on the experience of being within the Gezi protests.

Minsk Protests

From August 9, 2020 through summer of 2022 thousands of women, dressed in white, protested in “solidarity chains,” symbolically visualizing their peaceful intentions to stand up against the current political regime. Belarusian artist Rufina Bazlova’s ingenious red and white embroideries—evoking the visuality of both Belarusian folklore and the current protest movement—capture the most dramatic moments of the protests, such the crowd’s hailing of Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, who ran against Belarus’s dictator in the 2020 presidential elections. That year Belarus experienced the largest anti-government protests in its history.

The documentary play, “Insulted. Belarus(sia),” by Andrei Kureichik, is about the 2020 presidential elections, subsequent protests, and violent crackdown by Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in Belarus.

Mikhail Durnenkov’s 2017 play, How Estonian Hippies took down the Soviet Union

Read the PDF